John Lennon’s harshest critics would have to admit that he was, at the very least, a forward thinker. Even if he slipped into tone deafness, or hypocrisy, or just generally acted like an asshole, the man was desperately in search of something and always driven to shake things up rather than nestle into a comfort zone.

He was also, by no coincidence, one of those aforementioned harsh critics himself, maybe the toughest of all of them, when it came to assessing his own past work, both musical and otherwise. This was perhaps never clearer than in one of the last interviews Lennon ever gave, a feature story published in the September 29th, 1980, issue of Newsweek.

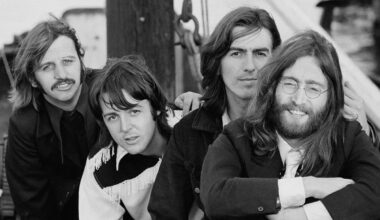

In that conversation, Lennon called his 1974 solo album Walls and Bridges a work with “no inspiration,” and shot down any thought of a Beatle reunion by expressing his general frustration with the beloved work they’d already done: “There are many Beatle tracks that I would redo. They were never the way I wanted them to be,” he said.

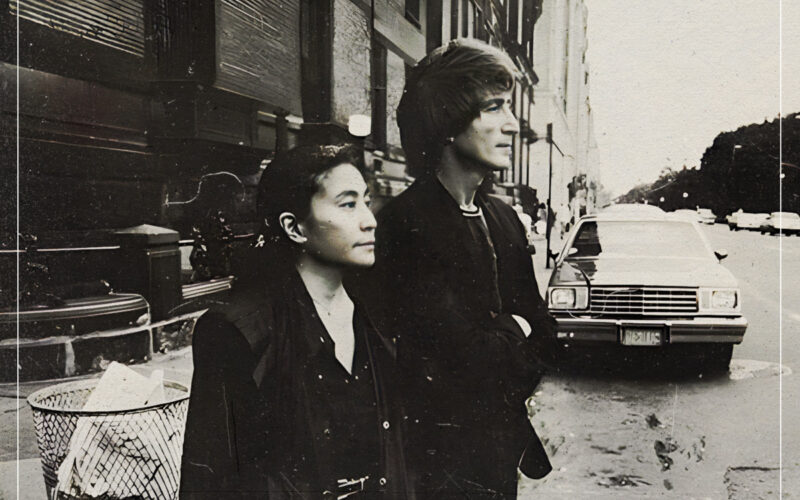

Maybe the most surprising regret Lennon shared, however, concerned his political activism in the early 1970s, when he and Yoko Ono were often putting themselves on the frontlines of controversial political debates, from the imprisonment of John Sinclair to the Attica prison riots to the feminist movement. During this period, Lennon had certainly alienated many of his original Beatle fans, but he’d also earned the more devoted and fervent support of people who appreciated the risks he was taking using his power and influence to speak for underrepresented groups and viewpoints.

With that in mind, it’s a bit sad to hear how Lennon, at the age of 40, looked back on those days less than a decade later.

“That radicalism was phony, really, because it was out of guilt,” he told Newsweek, essentially confirming a theory that many of his haters had long suspected.

“I’d always felt guilty that I made money, so I had to give it away or lose it. I don’t mean I was a hypocrite. When I believe, I believe right down to the roots. But being a chameleon, I became whoever I was with. When you stop and think, what the hell was I doing fighting the American government just because Jerry Rubin couldn’t get what he always wanted – a nice cushy job.”

John and Yoko had been close friends with the anti-war activist Rubin in the early ‘70s, but the relationship had soured, starting around the time that President Richard Nixon had launched an effort to get Lennon deported. After a long struggle, Lennon had managed to win his right to settle in America, but he seemed spiritually and creatively demoralised in the aftermath, retreating from politics and the music business to focus on his home life with Yoko.

Lennon had abandoned plenty of soapboxes before this. After fully embracing the hippie “flower power” dream in the late ‘60s, he’d tossed that idea aside when the movement was clearly becoming a parody of itself. A few years prior to that, while still a Beatle, John was still a borderline misogynist and homophobe with archaic thoughts about how relationships between men and women ought to work.

“I was a working-class macho guy who was used to being served and Yoko didn’t buy that,” he admitted in 1980. “From the day I met her, she demanded equal time, equal space, equal rights. I said, ‘Don’t expect me to change in any way. Don’t impinge on my space.’ She answered, ‘Then I can’t be here. Because there is no space where you are. Everything revolves around you and I can’t breathe in that atmosphere.’ I’m thankful to her for the education.”

As for whether Lennon should be judged more for the many mistakes he made or for the efforts he made to acknowledge them and move forward—that will always remain in the eye of the beholder.