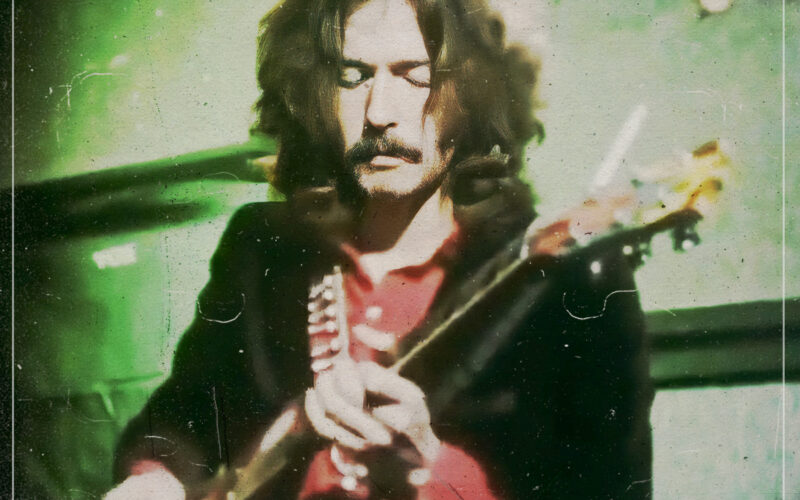

Like most of his peers, Eric Clapton built a career around authentic blues rock. “I wanted to be in Freddie King’s band or Buddy Guy’s band, that’s the band I wanted to be in – the real thing,” he once said. “I didn’t want to be in a white rock band, I didn’t want to be in a black rock band, I wanted to be in a black blues band.”

For Clapton, blues offered something entirely different, something that kept everything feeling fresh in an inexplicable way, an outlet away from stale, rock ‘n’ roll stagnation rooted in instinct. It gave him the same rush people like Keith Richards noted when talking about why he loved it so much to begin with, something beyond his love for jazz greats like Billie Holiday and Billy Eckstine and something more embedded, primal.

Perhaps that’s because blues always felt more like an attitude or mindset than a genre or set of musical structures, an opportunity to tear out the rulebook and just go on pure feeling, something musicians like Clapton could always come back to as a reference point when ideas failed to flow. At the same time, it wasn’t a separate entity, as it is easy to assume when looking at it as a standalone genre; it was something that flowed into everything, igniting the weak flames of rock ‘n’ roll into something explosive.

Perhaps that’s also why even those none the wiser to Clapton’s affinity for the genre can almost always pick out the influence, even if it’s in the slower, sluggish energy pulsating through the threads of heady licks and rhythmic beats that could only really have stemmed from one place in particular. It’s also undeniably why, when his lyrics and storytelling fall short, his instrumentals are intriguing enough to make up for it, as was the case with ‘Change The World’.

On paper, there’s nothing great about the song at all. In fact, Bernie Taupin once said it’s the song he refers to when backing up his point about a song not needing perfect, well-thought-out lyrics to be any good. “What sold that song, I believe, is production,” he told Musician. “And it had a good melody. But don’t listen to the lyric. Because the lyric is appalling. It’s a bad lyric. There are some rhymes in there that are really awful. But that’s not what sold the song.”

What Clapton did to make it work was take the original demo and pour hot, steaming blues-inspired lava all over it, giving it a more enticing umph that brought audiences from two different worlds. It also taught him a lesson in becoming his own reference, unintentionally creating a blueprint he’d revisit every project. As he explained to Mojo: “When I heard Tommy Sims’ demo. I could hear McCartney doing that, so I needed to, with greatest respect to Paul, take that and put it somewhere black. So I asked Babyface who, even though he may not be aware of it, gave it the blues thing.”

He continued: “The first two lines I play on that song on the acoustic guitar are lines I quote wherever I can and they come from the beginning of ‘Mannish Boy’ by Muddy Waters. On every record I make where I think. This has got a chance of doing well, I make sure I pay my dues on this. So I think I’ve found a way to do it, but it has to have one foot in the blues, even if its subtly disguised.”

You can hear those familiar threads in the track, the quintessential Clapton twang that comes through in almost everything he does, like an inexplicable bounce that stops it from falling flat, no matter how many times it’s reinvented. Suppose, in a way, that’s the exact type of blues Clapton became endeared to, the type that never gets old, always rooted in pure feeling, even if the basics remain the same.