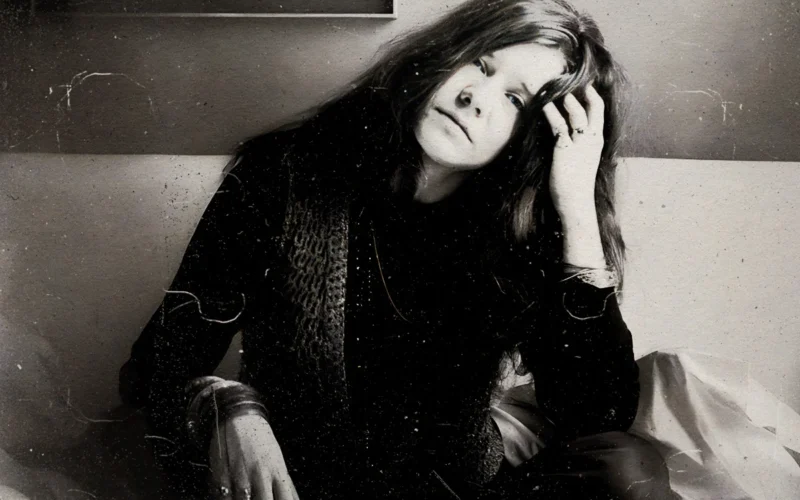

Judy Garland might not be the first point of comparison that springs to mind when one considers the brief four-year career of Janis Joplin. One was a Hollywood starlet of the 1940s; the other a hippie queen of late ‘60s rock and roll.

In many other ways, though, their stories echo one another. Each was the powerhouse female voice of their generation; similarly drawn to California from the middle of the country and ultimately plagued by demons of self-doubt and addiction.

Unlike Garland, Joplin wasn’t a child star, but at the age of 23, when she made the decision to leave her Texas home for good and seek her destiny in San Francisco, it was very much the equivalent of Garland’s Dorothy Gale arriving in the land of Oz.

After being seen as an outcast and a misfit during her days at the University of Texas—she was once voted “Ugliest Man on Campus”—Joplin had become convinced that there might be a place better suited for her out West. Her friend Chet Helms, a former University of Texas student himself, was her biggest champion and the primary voice summoning her to the Bay. Helms had seen Janis sing at clubs in Austin, and though she was often drunk on stage and uncomfortable in her own skin, her talent was already unmistakable.

Helms, it turns out, was a very useful friend to have. By 1966, he’d become deeply involved in the budding music scene in San Francisco’s soon-to-be-famous Haight-Ashbury neighbourhood and was managing a new band called Big Brother and the Holding Company. Helms only had one person in mind to become that band’s lead singer, and in the summer of ‘66, Janis Joplin accepted his invitation to join the group. She was excited at the opportunity, but also clearly struggling with feelings of guilt and doubt, as seen in a letter she wrote home to her parents shortly after her arrival in California.

“With a great deal of trepidation, I bring the news I’m in San Francisco,” Joplin wrote, explaining that her “old friend” Helms had “encouraged me to come out. Seems the whole city had gone rock & roll (and it has!), and [Chet] assured me fame and fortune.”

Joplin had neglected to inform her parents about her move beforehand, originally telling them that she was joining a band in Austin. As she confesses the truth in this letter from June 6th, 1966, it’s a remarkable glimpse into the internal mindset of a virtually unknown performer right on the cusp of superstardom. Within two years, she’d have a number one album, and just two years after that, she’d be dead from a heroin overdose at 27—frozen in time as an icon of rock.

“I just want to tell you that I am trying to keep a level head about everything and not go overboard with enthusiasm,” Joplin wrote. “I’m sure you’re both convinced my self-destructive streak has won out again, but I am really trying.”

Joplin assured her parents that she’d come back and get her college degree, unless her music pursuit “turns into a good thing.”

“I’m awfully sorry to be such a disappointment to you,” she added, heartbreakingly. “I understand your fears at my coming here and must admit I share them, but I really do think there’s an awfully good chance I won’t blow it this time. . . . And please believe that you can’t possibly want more for me to be a winner than I do.”

Four days after writing that letter, Janis made her debut with Big Brother & the Holding Company at the Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco, solidifying her as one of the lead voices of the new sound of American rock ‘n’ roll.